- Home

- Anthony Daniels

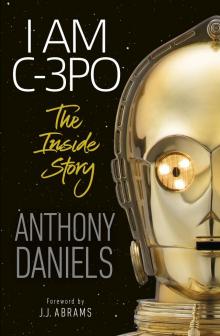

I Am C-3PO--The Inside Story Page 7

I Am C-3PO--The Inside Story Read online

Page 7

“We call him White Pointy Face.”

And I could see why. I was holding the face of a different sort of robot from the one I normally worked in. It was painted white and its features were indeed pointed. Props can be quite literal, at times. But who, or what, was this droid? The eyes gave it great personality. They seemed to be slightly crossed and staring. Whatever this droid was, I decided he was neurotic. Props explained that the character had been modelled on the same basic shape of my gold suit, so it should fit me. Really?

They dressed me up in this new weird garb. It was wonderful. The chest was much larger and actually allowed me to expand my own inside it. But as a fashion item, White Pointy Face wasn’t ever going to be a role model. He was not a stylish droid. In fact, he seemed to be wearing oversized underwear and generally, he looked a bit grubby. But everything was a bit seedy in that street scene. And I was quite happy being weird White Pointy Face. Of course, I wasn’t the only one looking weird in this scene. For instance, what was that actor doing perched atop a pair of feathered stilts?

EXT. MOS EISLEY SPACEPORT – ALLEYWAY – DUSK

ACTION!

The giant chicken legs passed directly across the lens. Obi-Wan and Luke hurried forwards, ignoring White Pointy Face, who was twitchily wandering down the street, trying to remember what mission he was on.

AND CUT!

That was it. White Pointy Face’s day was done – his five minutes of fame, over. Except they weren’t. Weeks later, I was back in my normal garb, shuddering inside a different set.

INT. SANDCRAWLER – PRISON AREA

I had to pretend that the whole thing was bumping over the sand dunes on Tatooine. Of course we were at Elstree, in what appeared to be a junk shop. It wasn’t actually moving at all. Decades later, I would relive this moment in another cluttered set, that really was getting jiggled about on a different planet – but the “treadible” had yet to be invented.

And as the sandcrawler, apparently, approached the Homestead, there he was, White Pointy Face, slumped in a corner. Since I was inside my other suit, he was lifeless, twitched only by fishing lines attached to his various parts and yanked by the crew. But at least he had five minutes more of fame. Until Return of the Jedi.

INT. JABBA’S PALACE – BOILER ROOM

Poor Threepio. About to be sent to Jabba’s sail barge, he is surrounded by droids in various stages of cruel destruction and torture. And as he leaves, there by the door, staring hauntingly, is White Pointy Face. Now fifteen minutes of fame, total. But it wasn’t over yet.

Many years later, game creators, Decipher, produced a character playing card. The image was familiar. But the name wasn’t. “CZ-3”. It seemed White Pointy Face was an insufficiently techno name for the current times. But as part of a card game – he had finally achieved immortality. Of a kind.

25 wrap

It was the last day shooting.

After twelve weeks or so, Fox were increasingly concerned at the contents of the dailies they were viewing back in California. They were understandably nervous at the money being spent – their money. So they cut it off. It seemed a desperate moment, strangely reflecting the story we were telling. But we did manage to grab this last sequence. It didn’t look much – just a wall with a small round window. I was told not to encroach on this viewport. It would mess up the visual effect shot of the view of the distant Tantive IV.

INT. ESCAPE POD

ACTION!

“Are you sure this thing is safe?”

But I had to get in there first. So here was another set – the hatch in the Tantive’s passage way. Days before, Kenny Baker had trotted inside. He was short enough to pass through the small door, wearing the top of an Artoo shell like an overcoat. He came out again and we shot Threepio side-stepping in.

It was frightening.

INT. REBEL BLOCKADE RUNNER – SUBHALLWAY

ACTION!

“I’m going to regret this.”

I took in a breath and bent over, low enough to pass through the doorframe. The bottom edge of Threepio’s chest pushed deep into my diaphragm. I shuffled forward and inside. The door slid down. I literally couldn’t inflate my lungs. I couldn’t breathe. They wouldn’t realise outside. It seemed Eternity had truly begun for me.

AND CUT!

The door slid up. I shuffled out. Fast. We did several takes. It was scary. Every time.

But now it was all over. Filming was finished. Suddenly. Stop. It had been a rather peculiar experience. None of us seemed clear on what we had done. I certainly doubted that anyone would watch our efforts. It all seemed a bit of a mess. I’d certainly had enough of the physical side of it all. And the emotional side too. I wonder if I would have agreed to be part of it if I’d known just how much sheer effort it would take. And I could only hope that I had made a reasonable job of the character. Nobody ever said anything either way. Everyone else had worked hard too. It was just that they had the chance to sit down. I had grown fond of some of the cast and crew but the entertainment industry is full of hellos and goodbyes and hugs and promises to keep in touch. Everyone has their own private life. Working together doesn’t mean you’re wedded at dinner, weekends and when it’s all wrapped. And this was a wrap. The purse strings had pulled tight closed.

That was it.

Or so I thought.

26 stunned

Months had passed and I’d put the whole experience of filming The Star Wars out of my head.

Then a phone call. They needed me to go to America. California. HOLLYWOOD. To record Threepio’s voice for the finished film.

I’d never flown that far, never had jetlag. I was in mild shock – possibly the lengthy wait to get through immigration, the suffocating feel of the warm air, my first sight of the iconic flying saucer restaurant at the airport, the untidy mass of overhead power cables, the huge billboards screaming their wares, the nodding donkeys, eternally pumping oil. I arrived finally, in a rather bland hotel room, with a whirring air-conditioning unit and brown furniture. Barely unpacked, I fell asleep.

Awake, well before dawn, I stared out of the hotel window, hearing the bleakly alien police sirens screaming down the street. I was famished. It wasn’t the sort of hotel that had a minibar with snacks. Anyway, they would have cost too much. If there had been room service, that would have been a terrible extravagance. My stomach just knotted itself. Later, I would find a Ships Coffee Shop down the road – open 24 hours. Who had ever heard of that! The rest of the world woke up and I eventually managed to hail a Yellow Cab, a minor miracle – they were going bust and so in short supply at the time. This, combined with my time-zone challenge, made me nervous as I sat in the morning commute. Would I make it in time? It would be distressing to come all this way and be late. Actors are neurotically punctual, or early, or someone else might get the part.

Eventually, we arrived at Hollywood and Vine. I paid the cab driver, carefully sorting the dollar bills, so new to me – all the same size and colour – too easy to make an expensive mistake. I rather tentatively pushed open the office doors of the Sound Producers Stage building. They’d been expecting me, and I wasn’t late after all.

The mixing suite was certainly imposing, with its big screen and huge console of buttons and switches and lights – more impressive by far than the Falcon’s cockpit. The technician was twiddling things, adjusting other things. He greeted me warmly.

“You must be Anthony.”

He pronounced the H in my name. It sounded so odd to me but I let it pass. Everything in this country was going to be a surprise.

“Welcome. You know, it’s amazing that you got here. We’ve spent a couple of months trying to find a voice for your character, ’cos George really hates your perf… Oh. Hi, George.”

I was shocked. I didn’t even say hello.

“You hated my performance?”

George looked abas

hed.

“Well, I… err… never thought of Threepio being a British butler.”

I was stunned. He could have said something at the time. I could have done it differently. I could have offered something else.

It transpired that thirty actors, including stars like Richard Dreyfuss, had been invited in to dub my on-screen movements. Many talented people gave it their best, but nothing had quite fitted the character as I had physically created him. Finally, a voice-over pro pointed out that my vocal performance was actually okay. Exhausted with the quest, George had generously changed his mind.

This was my first go at “looping”. As each line played on screen, with the original guide track, a second film went by a recording head. There were no pictures on this film, just three stripes of magnetic tape. A system of rhythmic clicks told me when to start – on the fourth click – which wasn’t actually there. It was imaginary. The film was literally stuck end to end, in a loop, so it could go past the recording head as often as required. However, I only had three goes at syncing my new voice with the projected picture, before they had to over-record a previous attempt. They could always put up another blank loop, of course. I was fascinated, but it took a few attempts before I relaxed enough not to worry about the mechanics of it all. I was watching my own mechanics on screen. This was the first time I saw what everyone else had watched on set – me – as Threepio. Gosh!

It was a lot easier saying the lines wearing jeans and a shirt. I have always had a non-regional British accent – a bit posh, I suppose. I enhanced it to give Threepio an exaggerated, servant personality. Perhaps, being surrounded by so many American voices gave me a sense of contrast. The script made it obvious to me that the character was nervous, pernickety and uptight. Voices tend to go to a higher range under such circumstance. I sent mine a bit further backwards with a tensed throat. And I would literally make myself uptight. Buttocks, diaphragm, throat – everything clenched. Whereas I slouch a little, like most humans, Threepio is very upright and correct. And tense. And robots don’t breathe. In performance I had to get out the words on one lungful of air – when available. Of course, gasps could ultimately be removed in the edit. But part of his personality comes from his impatient, pacey delivery. George always liked things faster.

I also spoke very precisely, making this talking machine sound didactic. It gave the character a pedantic personality that was just a little off human, emphasising his inability to read certain inter-personal situations.

That first day in the desert, they had stuck a small microphone above my face, just before they locked me into the head. A wire ran down my back to connect to a transmitter, ignominiously shoved in my pants, the only place there was any room. The audio results were awful – miles of magnetic tape of nothing but grunts and groans and expletives; the muffled lines almost unusable as a guide track. They soon asked me to re-record the words immediately, without the head on. A wild track. I was more than happy. I replicated my original performance, and the editors held on to their sanity. For me, anything without the head on was a bonus.

Now, finally, it was me standing there gazing at the screen, waiting nervously for the fourth click that would cue me to speak my line. Watching this curious metal man in a silent, black-and-white world of 35mm loops, didn’t grab me. It was all rather flat – no sound effects – no atmosphere – just me.

Then we reached a sequence where George had added a temporary music track. A piece of Ravel’s Bolero. What a transformation. Suddenly the scene had drama, interest, tension. I had never considered why most films add a score. It changes everything. I was amazed by the power of this music to alter the mood. And I hadn’t even met John Williams at this point.

George did beg me to do one thing.

“If you say shed-uled, like you did on the wild track, no one in America will understand what you’re talking about.”

I was surprised. Was there another way to say the word in the English language? Apparently so – in America. As a small gesture of forgiveness for George nearly excising my performance from the film, I wrote a big letter K on my script and held it up in front of the screen. The cueing system clicked at me to start talking again.

“Level five. Detention Block AA twenty-three. I’m afraid she’s sKeduled to be terminated.”

“Terrific.”

George was clearly relieved – and grateful.

Lunch on day one was a crisis. He took me next door to a burger bar, Hamburger Hamlet, I think. Used to the feeble Wimpey offerings back at home, I was astounded at the stuff you could pile onto the standard bun and patty – “fixings”. We placed our booty at a table and sat. My finished stack was quite tall. I picked up a knife and fork, to stab the top. George went into amused shock. I was embarrassed. He taught me to grab the whole thing in my hands, squish it together and chow down. It was the best. Rather stuffed, we went back to the studio and I talked for the rest of the day. But then came embarrassing moment, number two. They found a cab to take me home. We drove off into the heavy traffic, as I spoke.

“Please would you take me to the Holiday Inn.”

“Which one?”

In my days as a naïve traveller, it never occurred to me that there could be more than one hotel of the same name. I had no concept of the bigness that is Los Angeles. I had been awake since two that morning and was worn away by the day’s effort. I rather pathetically said I thought it was towards the sea. We drove west. Eventually I saw an Inn that wasn’t mine but we pulled over. The staff were very understanding and phoned around. It seemed I was a guest at the Westwood branch, on Wiltshire. I always get an address card from any hotel I stay in. Well, I do now.

In post-production, Ben Burtt, the brilliant inventive Sound Designer for the whole, and I mean whole, project took my finished vocal performance and added a small electronic element – a little tweaking of the tonal balance and a few thousandths-of-a-second of digital delay. The treatment gave my words a sort of low grade, transistorised quality. He then went to the trouble of playing my voice back into a suitable environment and re-recording it.

At some point during editing, they phoned me. Would I do them a favour? Would I please go to a studio in London and record an extra line? Of course. What was it?

“That’s holding the ship here.”

“Is that it?”

“Yes. We forgot to say what a tractor beam is actually for.”

Ah.

“The tractor beam, that is holding the ship here, is coupled to the main reactor in seven locations.”

It was one of the quickest jobs ever but it worked, once they plopped in the new words. The audience would never know the line was compiled over five thousand miles, and many weeks, apart.

I always stand upright in the recording sessions. Guests smile as they watch me in a typical Threepio pose – arms out, bum clenched, attitude. They can see the character, standing before them. The voice became iconic in its own right. Parents often ask me to do it for their children, who don’t quite believe them. After all, any old man can claim to be the guy inside the gold suit and kids are rightly sceptical.

“Hello. I am See-Threepio, human-cyborg relations.”

Then I see the magic. I watch as the sound enters their ears, it reaches their brain, it gets processed in moments. And suddenly. Smiles of recognition – and love.

27 survival

My work was done.

It had taken three full days in the studio but finally I had spoken my last words as See-Threepio. I had no idea what the finished film would be like – or if anyone was ever going to watch it. The black-and-white clips I had voiced seemed rather flat. Music and effects would be added later. Maybe that would help. But now I was flying back to London. My extraordinary American experience was over.

It had been a treat to visit a country that I’d only observed through the movies. Many of the streets looked familiar, from having see

n them on TV. The whole of Los Angeles was a stage set, really quite bewildering in its immensity. And yes, there was the Hollywood Sign, a little run down but still iconic. Yes, they had all-night eateries, diners did ask for their eggs “sunny side up”, and the TV was nothing but commercials – and people did say “Have a nice day.” It had all been rather alien, though the immigration signs at the airport had cast me in that role the moment I arrived, pointing me to the appropriate queue – or “line”, as they put it. Now I was going home to a land where I knew the rules and vocabulary. I had finally seen the USA. I think I liked it. I didn’t expect I would ever return.

Then – for months – nothing. Complete radio silence from Lucasfilm. I had put the whole mixed-bag experience out of my mind. I would never forget my trip to the States earlier that year but I had moved on, and back to a more normal life of trying to find other work.

I saw it on a shelf in my local newsagent – the cover of Newsweek, or maybe Time, or maybe both. I forget. I could read the banner headline without even picking up the magazine. It shouted at me. To my surprise, in every sense, the strange little sci-fi film was clearly a colossal hit.

I eventually saw Star Wars at a crew screening in London. The huge Dominion Theatre was packed with so many familiar and unfamiliar faces. The crew was fairly large and most had brought along friends and family. I imagine the team were wondering what they were about to see. They’d certainly been dubious at the time of shooting – doubting that this weird American production would amount to much. The atmosphere was jolly enough. The crew were simply waiting to see the results of their hard work.

The lights dimmed as the gigantic curtains smoothly slid apart, the screen widening to its 70mm vastness, the auditorium hushed. In the silence, a strange message appeared on screen.

“A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away....”

John Williams’ main theme crashed in. We were hooked.

I Am C-3PO--The Inside Story

I Am C-3PO--The Inside Story