- Home

- Anthony Daniels

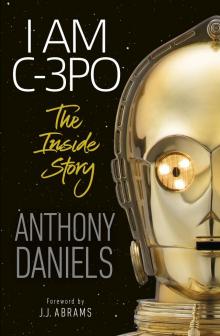

I Am C-3PO--The Inside Story

I Am C-3PO--The Inside Story Read online

I am

C-3PO

Anthony

Daniels

Foreword by

J.J. Abrams

author’s note

A friend of mine is fluent in more than six million… oh, you know the rest. Personally I’m only fluent in English, as it is spoken round the corner from where I live. Since you know my voice, I’ve made the decision not to adopt American spellings here, but to keep my words in the original. I hope that’s OK.

(Translations are available on the Internet or from your local human-cyborg relater.)

For

my amazing wife

Christine

with love

and for

Howard

(who is also rather amazing)

and of course for

You

contents

foreword

1love

2captured

3plastered

4promises

5ladies

6dogs

7action

8object

9control

10envy

11tricks

12tears

13damage

14escape

15clunk

16tensions

17 doors

18 embarrassments

19magic

20 steps

21 pyros

22 trash

23 game

24 fame

25 wrap

26 stunned

27 survival

28 special

29 identity

30 puppets

31 mop

32 illusion

33 cake

34 Christmas

35 blind

36 beep

37 caged

38 gloop

39 panic

40 torment

41 bonfires

42 ride

43 radio

44 smoking

45 naked

46 celebration

47 tchewww

48 relationships

49 officer

50 green

51 exhibits

52 merch

53 forgery

54 red

55 rogue

56 lost

57 Carrie

58 droids

59 dread

60 joy

61 maestros

62 friends

63 heroes

64 closure

droidography

credits

copyright

foreword

I want to talk about Anthony (as does Anthony). But I need to give this some context. Let’s start with the obvious. There’s magic in Star Wars. In all of it. From the design of the logo — those outlined letters against the stylized star field — to its aesthetic, production design and delicious combination of Flash Gordon space adventure and Kurosawa samurai high drama.

There’s magic in its enhanced real-life locations, gorgeously unique props and ships, sound effects and, of course, its breathtaking, instantly-classic musical score. But would we be considering — or continuing — a story that began nearly half a century ago if, at the heart of it all, there wasn’t such a powerful sense of humanity? Surely even the genius of the lightsaber and the growl of a Wookiee would have been long forgotten if George Lucas hadn’t focused so ingeniously on the souls of the main characters. It was their desires and desperation, their fears and revelations, their love and loyalty that made Star Wars a saga for the ages.

The most potent aspect of Star Wars is evident from the opening minute of the first film. After announcing that it’s a once upon a time fable, after the blast of unforgettably powerful music, after the thrilling crawl gives us its pulpy context, and after the awe-inspiring Star Destroyer passes us overhead and the small Blockade Runner is revealed, we cut inside to see members of the Rebellion, rocked by the attack. But what happens next is what’s most important. We fall in love.

Nearly the instant we meet stalwart droids C-3PO and R2-D2, we laugh. They become our way into a galaxy we’re so desperate to be part of. Their fear, their bickering, their frantic need to survive is what grabs us by the heart and allows us to be mesmerized, to be taken on the cinematic adventure of a lifetime. Despite all the wondrous spectacle and artistry, the characters themselves are the glue that keeps Star Wars together and us stuck to it. Among them all, only two characters have appeared in all nine saga stories. Those two droids I first met when I was ten years old.

While I suspected that bringing Threepio to life was harder than it looked, experiencing it first-hand gave me an instant, newfound respect for the man with the golden eyes. It turns out that being inside that sensory deprivation tank of a costume is a challenge at best.

Moving, hearing and seeing is only part of the problem, as the actor playing Threepio needs to constantly interact with numerous other performers in a scene with deft, seemingly effortless comedic timing. That actor is, of course, Mr. Anthony Daniels. A gloriously witty, keen and spirited man who may be the least-recognizable superstar on the planet. When I first called Anthony about appearing in The Force Awakens, I asked if he was willing and able to return as everyone’s favorite humanoid droid. His enthusiasm to do so was heartening. But — and I’ll put it bluntly — would he be able to fit in the suit? When I met Anthony and saw that he was in better shape than I will ever be, I was enormously relieved — as was he that a new, more comfortable suit was going to be fabricated by costume designer Michael Kaplan and his team.

In The Force Awakens — where Threepio remained mostly within the Resistance base — perhaps Anthony’s biggest challenge was the red arm (I gave Threepio a new limb to demonstrate that the character had gone through some dangerous adventures since we’d last seen him. Anthony hated it. Hated. Like... hated. As you will see). In The Rise of Skywalker, however, Threepio is out on the wild journey with the others. That means ships and speeders, deserts and snowy villages, climbing, crashing, and encounters with some terrifying creatures. With this, the challenges for Anthony rose exponentially. But every time they would remove his mask (wearing the suit, he is unable to do that himself — just think about that), there was Anthony, his face sweaty and smiling. Much like the droid he so beautifully, artfully portrays, Anthony wanted to be out on the adventure again, too.

The cast and crew of these recent films were well aware of the stakes involved in creating a third trilogy. How important it was to do well by the legions of Star Wars fans, continuing and concluding George’s remarkable tale. As surreal as it still feels to know that I’ve directed two Star Wars films, I could not begin to imagine what it was like to have been there before, again and again and again, for all of the Skywalker saga. At least I couldn’t until I read this insightful, delightful book.

The stories you’ll find in the following pages come from one of the most unique perspectives on Star Wars that could possibly exist. It is ironic that, despite Mr. Daniels’ limited field of vision (peering through those two slit and lit holes is the visual equivalent of breathing through a straw), this book takes a remarkably wide and deep view of the film series. Why is it that we fall in love with Threepio the moment we meet him? My humbling experience on these films has given me the answer: It’s because there’s a man inside. A most excellent man, who — I’m happy to say — you’re about to meet yoursel

f.

J.J. Abrams

Los Angeles, 2019

1 love

It was the best job I ever had.

The story came alive every night, in front of thousands of devoted fans. Across countries and continents around the world, I narrated a finely honed script that spoke of the key moments in our beloved tale. This was Star Wars – In Concert.

I stood, smart black-suited as myself, absorbing the power of it all. From 2009 – from Houston to Hamburg, Tokyo to Tulsa – I was enveloped in lights and laser beams, dwarfed by the symphony orchestra and choir behind me. The giant screen, backdrop to our arena stage, reminded us all of what we loved, with sequences edited around epic themes. The Villains. The Heroes. The Princess. The Battles. And John Williams’ glorious scores played live to picture. It was huge and inspiring. I had the best seat in the house standing there between the orchestra and the audience. I felt the power of the images, the power of the music. But the power of something else, too.

I had never truly understood the devotion of the fans, their adoration of the whole thing. Being so involved, I was too close to really appreciate it all. Now, I began to see past my own myopic stance and view the Saga reflected back to me by the faces filling the arenas. The vibrant sense of respect, of affection, of love, that flowed across the footlights was palpable. Love for the music, love for George, love for the actors on screen and some small element that made me feel loved too. It gave me an understanding of something that had eluded me for so many years.

I wish there were another word for “fan”. It’s an abbreviation of fanatic. But most fans are simply gentle admirers. They aren’t crazy or nerdy. But maybe it is the best shorthand term for all those who really made Star Wars the phenomenon that it became. Without the fans, A New Hope would have been the beginning – and the end.

2 captured

It was all I ever wanted to be.

From the time my parents would hold me up to pull the draw strings on the small window curtains at the top of the stairs, I was fascinated by the simple mechanism that opened them. Like the reveal in a theatre’s proscenium arch, they gave a hint of the magic beyond; a magic that ended by pulling the other string that closed them. I was allowed to repeat the trick many, many times. If I connected this with acting, it was unconscious, but we did regularly go to the theatre. Maybe that planted a seed. Did five-year old me excitedly running down to the stage to shake the paw of an actor dressed as the Cat in Dick Whittington, a Christmas pantomime, did that unrestrained enthusiasm predict my eventual role, acting in a suit? Because that was all I ever wanted to be. An actor.

Time passed.

I was lucky. I had a métier. A calling. A passion. Something I needed to do in life. An ambition. So many young people have no idea what they want to do. I feel for them. I always knew what I wanted to be. It was easy. If only it had been as a doctor, lawyer, banker, teacher – classic professions – then my parents would have approved. They didn’t. They gently dissuaded me from such a perilous thought. So I tried to be a lawyer. For two years. Twenty-four long, long months.

Being a member of an amateur dramatic society kept my sanity and my longing alive. Standing in the wings of our tiny stage, waiting for my entrance as the stage manager pulled the strings to part the proscenium curtains, I murmured.

“I wish I were an actor.”

John Law looked at me – a teacher by profession.

“If you want to be an actor, be an actor.”

We walked on stage together.

It was that simple.

But it would be three more years before I finally had the courage to take his words and admit that my life was unfulfilled, pointless, unless I followed my dream.

I was twenty-four years old before I took myself to drama school.

For three years I learned a little of this and a bit of that. The curriculum was mostly geared towards the theatre. That seemed enough. To have considered film might have appeared presumptuous. Of course there were acting classes and improvisation. The latter still scares me but how useful it would be later. Mime classes too – they were fascinating; isolation techniques, fighting with imaginary forces to restrain an imaginary umbrella in an imaginary gale; trying to deliver emotion, wearing a blank white mask. Then there was voice work; vocal exercises, projection, diction, tongue-twisters, bi-labial fricatives. Stage fighting, ballet, text analysis and growing up.

I graduated with a job with the BBC’s Radio Repertory Company. A huge, overwhelming joy to me. Not just the accolade of winning their annual Carlton Hobbs Award and performing in so many of their productions – but the gift of a union ticket – an amazing thing back then. No membership of Actors’ Equity, no work – no work, no Equity membership – without struggling for months – years. Now, the acting profession, quite rightly, is open to anyone who has the courage to put themselves forward and try. And of course the opportunities to work in entertainment have vastly increased, for the amusement of viewers and the employment of so many more talented players. Back then there were a few TV channels – no cable – no Internet. Unimaginable now.

Then, my sojourn with the BBC over, I began to clamber forward on stage and television in minor roles. My luck held for the next two years. I was thrilled to be playing Guildenstern in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, by the exceptional British playwright, Tom Stoppard.

The phone rang.

I was there to pick it up. To leave the flat unattended was a brave gesture in the days before answering machines. In the decades before mobile phones.

I listened.

“No. I don’t think so. Thank you.”

“Don’t be so stupid. Go and meet him. You never know what it could lead to.”

It was 1975.

The 14th November.

12.30.

I hadn’t wanted to meet an American film director called George Lucas, to discuss the role of a robot in his low-budget science-fiction film. I wasn’t a fan of the genre and probably thought it was beneath me. I was a serious actor – and had been for the two years since I left drama school. But I obeyed my agent and walked through the traffic to 20th Century Fox House in Soho Square. It was only a short distance from the theatre in Piccadilly Circus where I was performing at the time. I had never thought of being in a film. I was comfortable acting on stage. Filming seemed huge, Hollywood and out of my reach. But here I was, pushing open the front door with the famous Fox logo above me, as I entered the marbled interior.

The receptionist had the air of someone who’d seen it all before – especially seen actors entering in hope and leaving crestfallen. I must have seemed an anachronism as I casually said why I was there. She directed me upstairs and I found the appropriate office. I explained myself to the rather more interested secretary who was guarding the man himself. He was behind the other door in her room. She knocked and I entered the lair of, I supposed, a cigar-chomping, overweight, loud Hollywood movie mogul.

There was George.

Jeans. Plaid shirt. Diminutive. Shy. Polite. Exhausted. He was seeing hundreds of actors.

We sat down.

There was a pause.

“So. You’re an actor?”

“Err, yes.”

“And good at mime?”

“Well, quite good.”

I had been brought up in the useless English tradition of self-deprecation. I was shy too, but feigning polite interest in this weird project. During a rather desultory conversation, I noticed, what I would learn, were concept paintings, decorating the office walls. George led me to one in particular.

I stared.

My world stopped.

My diffidence fell away.

I was entranced.

Captured.

Bonded.

Ralph McQuarrie had created an evocative image that touched my soul.

Standing on a san

dy terrain, against a rocky landscape, with distant planets filling the sky, Threepio gazed out forlornly. Our eyes met and he seemed yearning to walk out of the frame into my world. Or, I felt, for me to climb over and join him in his. I sensed his vulnerability. Maybe he sensed mine. It truly was a strange moment.

I went home to rest before the show that night.

They delivered a script the next day.

The Star Wars.

There was a small sticker on the front – colourful in blue – triangular – a young man holding a kind of sword. It suggested drama.

I opened the paper cover.

In my innocence, I had never seen a film script before. It was immensely complicated. Obviously nothing was linear, as the action jumped around from scene to scene. And the pages were packed with alarming stage directions and stuff about POVs – points of view. The only thing I really understood was that See-Threepio had been gloriously conceived by George and the scriptwriters. The poor creature was always out of his depth – always in the wrong place and battered by events beyond his control. Programmed for abilities that would rarely be required in such a violent world, his frustrations were increased by his close and loving friend, Artoo-Detoo – Threepio reticent and self-protective – Artoo gung-ho and inquisitive – their affection for each other so clear in its understatement. It was a master-class in odd-couple scripting. Their banter was delightful. Their menial and meaningless place in society was classically tragic.

I was hooked.

Forget it was sci-fi.

Forget Luke and Han and Vader.

Threepio was the one for me.

Back at 20th Century Fox the next day, the secretary asked when I could go to be cast. I was confused. I said that’s why I was there. Now. She gave me a rather quizzical look as she opened the door to George’s office again.

George looked more relaxed.

On the other hand, I was a little more nervous as we sat and discussed my lack of faith in sci-fi. I admitted that I’d actually asked for my money back when I walked out on 2001: A Space Odyssey, some years before. The cinema manager had simply but rudely told me to get lost. Quite right. Years later, I would meet Keir Dullea and Gary Lockwood, two of the stars of that film. They told me that a lot of people walked out. But before I had left that theatre HAL had made a lasting impression on me. A red light bulb and Douglas Rain’s hypnotic voice – an early warning of the dangers perhaps inherent in artificial intelligence.

I Am C-3PO--The Inside Story

I Am C-3PO--The Inside Story